What does Valor look for when we write a first check?

I’m going to take you back with me more than 15 years into my past when I tried to raise a seed round and failed. Then share every metric we use–there are only six. That way, you’ll not only understand what I’m looking for you, you’ll get a sense of why, too.

Why some founders don’t raise seed rounds

My excuse? I was too busy building my business, and the numbers VCs wanted didn’t matter. Life has schooled me since then, and I love school. I hope you get some learnings from my experience, so you don’t have to learn the slow way I did.

When I went to talk about my software, I was asked about revenue growth, recurring revenue, CAC, LTCV, burn, and churn. I thought my business so unique, at just over $1M growing 20% a year, that some of those numbers shouldn’t quite apply. I wanted to “sell past them.” I was good at sales and figured I could do that. I also had no idea what CAC was (rhymes with “hack”) and didn’t want to show my ignorance, so I didn’t ask –and didn’t know how to google “cack.”

However, fast-forward to now, I’m nothing if not a learning organism. 🙂 Bet you are, too.

Why VCs and founders sometimes disagree on the value of startup metrics

Most VCs have never run a business and don’t “wing” risk like us entrepreneurs do. They measure it. To back you, generally speaking, VCs, including Valor, must know you’ll be able to manage risks. Not all entrepreneurs are ready for that. I wasn’t. I kept talking to VCs, waiting for one to understand my amazing individual business and why I didn’t have the time (or really, systems) to track things like LTV and CAC.

While they all wished me well, and agreed there was a growing software business under the hood, there wasn’t enough “meat” for them to bite into. I was great at running payroll, sales, optimizing my web site, getting software out, paying my bills and contractors, hiring, firing when I had to, negotiating a lease–so many things I WAS tracking. The added layer of complexity–I just didn’t have brain space. To some extent, I also remember feeling it was all in my head just as accurately, or more so, than in any system. So I felt negative inspiration, so to speak, to put what was ‘more current’ my mind, in systems that were going to be behind.

Now, I know how. Some of it I started doing just because I needed to scale my business. For those raising seed rounds, you do it so you have a realistic, numbers-based conversation with potential partners. They don’t have your gut. You give them the next best thing–metrics. It’s not that hard. I’m writing it for you, in case you think it is.

6 simple startup metrics VCs need to lead seed rounds

1. Revenue, and revenue growth. This is generally MRR or ARR or API use.

To get to this, you just need to enter your customer bookings and billings timely. I know–sometimes it’s hard to get invoices out on time. Or import the credit card info timely. But do set it up. Hire someone on contract to do it –once– if you need to. You have to have significant historical revenue recognition, timely, without you having to put your fingers on it.

If you sell more than one product (like software, and implementation) then you need to book these as separate and stay consistent. The sooner you do this, the easier it will be. The longer you put it off, the more months you’ll have to pay someone (or sit with it yourself) to log. Use Quickbooks Online or Xero or even Freshbooks. Just do it.

If more time with your books is just your idea of slow death, many private CPAs can help you. A larger firm, but still valuable for projects like these, is Acuity. I am sure you can think of more. Any local entrepreneurs circle will have a few tech-forward accounting contractors near at hand.

2. Revenue growth.

If you do #1, revenue growth calculations are a snap. It’s just pulling a report from your Quickbooks or Zero on revenue growth. This is a standard report. Take a moment to configure your system, and tell it to generate that report for you every month (or week) and email it to you. Mmm, yum! Now we’re looking at growth.

The pushback the founder in me had to this was visceral. I knew I understood our growth. I got weekly emails from GA, our CRM, and our web forms telling me everything I wanted to know around key visitors, keyword performance, conversion to leads, leads to contracts, and contracts to close. I was in it. For me, last month’s revenue growth over the previous, or this June compared to last June, was a dry and useless piece of information. What I needed to know was, would that next big contract close and are their people crawling my site? I did know that–I had those digital eyes on stun.

- who you hire,

- how fast you hire,

- how many people you hire, terms you offer, and

- gives you that “dry, objective” perspective that can be hard to feel in the subjective hustle of early stage growth.

VCs want to be that informed, sober judgment side for you. It can be a great complement to you and give your people today–and the people you hire tomorrow–confidence in the business. Confidence calculates into efficiency in hiring, managing and strategic decision making. For example, when you ask a top talent to take a cut in pay–but a point of two of equity–to join you, numbers like these make the case.

VCs are not with you in this quarter, from a mindset perspective. When they offer a term sheet, they are making a decision based on what they think you can sustain for 8 or 12 quarters. If there is nothing to project from, there’s little chance they can build a case to invest in you.

3. Customer Acquisition Cost (CAC).

If you do #1 and #2, you’ll be able to handle #3. One of the reasons this stuff is so annoying is, it does build on itself. If you don’t respect the basics, you’ll never convince professional pockets to pay you a fair price for your equity.

I recently had a successful founder with over $5M in ARR tell me CAC was smack. He just didn’t believe it applied to him. That’s pretty typical. First off, it’s not a hard and fast rule–it’s a calculation. So yep, it applies. You do it by dividing all of your sales and marketing costs over the number of customers you got in that time. Whoa, does that make sense? No, not from a business operational standpoint. You and I both know that you can’t say what the cost was to acquire a particular account (unless you are a pure AdWords acquisition style business). Some take high-end dinners or a round of exclusive golf, and some just drop in from the Interwebs. On the field of battle, it seems and it is highly variable.

CAC helps the whole group of partners around you get a sense of the “average.”

Another thing the founder in me hates about CAC is it’s just inaccurate in that the costs (the marketing and sales expenses) actually apply to your NEXT customers and not the ones you just recognized. It’s maddeningly out of calendar sequence. And that is JUST the kind of thinking that kills your fundraising, because, now speaking with my VC hat, we don’t care about that level of accuracy. We’re assessing risk. Specifically, the risk and efficiency in how you see sales and marketing relative to revenue recognition. For that, CAC is elegant and easy. Just do it. Over time, over quarters, you’ll be annoyed but you’ll come to agree it’s a functional measure of your overall customer acquisition engine. And nothing beats it for easy.

EXCEPT…if you don’t code your costs. Oh yes, I see you–with you and salespeople working from credit cards, it can be a pain to account for the real costs of sales and marketing. Start with the more “fixed” costs of your marketing infrastructure and marketing stack. You’ll have half a dozen pieces of software, maybe a trade show booth, Adwords, marketing consultants, web site costs, etc. Code them all to marketing. Then, insist on anyone with a credit card coding their receipts before they get sucked into your accounting system. I hate doing this as much as anyone, but one evening a week, while you’re on Hulu or something, pull up the credit card’s mobile app and code every expense. Yep, just do it. Then you or your accountant can use the codes to set up and email you a monthly CAC report, showing your YTD trend against last year’s. Gonna be so good!

4. Long term customer value (LTCV).

This one is just how long a customer stays with you and how much they buy over theirlifetimee. It’s pretty straightforward to project quarterly. You would think you do this by actually tracking your revenue by account. Nope, like a lot of VC math, it’s not quite business-accurate but it is perfect on trend. This is a crucial thing to accept about VC math when you’re a founder. For you, LTCV is derrivedin your head, actually thinking about the customers you know–and probably, the ones you know who are in the pipeline and sure to close.

No one can tell you that you are wrong about that, but it’s not a number others can work from. As you scale, it’s important to be able to share easily derived numbers So here’s how VC math works on this one. You’re going to hate it as a business guidance metric, but just think it through because its value is not in accuracy “today” but in showing accuracy in trend. Trend is key.

- Take your total revenue from customers (by product if you have more than one) over a time period, like a year or a quarter.

- Divide by the total number of purchases. If you have 12 customers, and they are on annual contracts, you would divide by 12. If you have 12 customers, and they have monthly contracts, you divide by 144. Like that.

- Get the purchase frequency by dividing the number of purchases by the number of customers. So if you have multiple contracts with one customer, you’ll need to make sure you track sub-accounts. This can be annoying the first time–but it’s all about building a system that can scale forward, and so . . . just do it.

- Turn the purchase frequency into a purchase frequency rate. You divide the number of unique customer purchases (ie, enteprise customer and all sub accounts) by the number of customers in that time period.

- Multiply the average purchase value by the average purchase frequency rate. This is CUSTOMER VALUE.

- Now, you can get the lifetime value by multiplying customer value by the number of years a customer continues to purchase. Early on, yep, you make it up. Later on, the truth will clarify.

You can do tons of things with this number, but that’s another blog post. Again, when you first calculate it, it may not be useful to run your business today. But it should be critical in running your business in two years–so you:

- build the system first,

- show the system is there, and

- that’s how you get the money to scale.

It’s the ultimate application of “show don’t tell.”

- Burn.

Burn is another term that’s often annoying to founders. As an operator, you know two things:

- It changes

- It’s in your control. You can cut burn as fast as you can cut your salary or accept that next offer from an accelerator for $50K or $100K.

Since you feel in control, it seems sort of pointless to talk about it in too much detail. You’ve got it.

The VC has no problem trusting that. However, to make the same point again, the VC you want is looking to add value to your business by studying meaningful trends and examining risk at a level the CEO won’t (it would take too much time away from the business). This makes a great VC a great financial partner (not an operational one).

Burn is easy to calculate, but in VC-ese, a language where we have more acronyms than an Army supply officer, it comes in several flavors. Here are three:

- Hype Ratio = Capital Raised (or Burned) / ARR

- Efficiency Score = Net New ARR / Net Burn

- Burn Multiple = Net Burn / Net New ARR

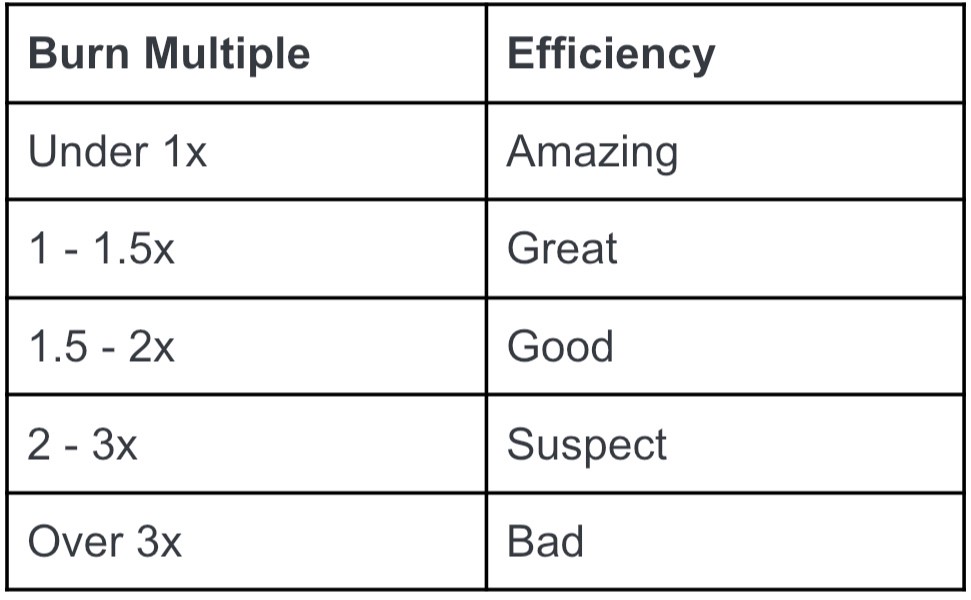

Craft Ventures has a great post where they write, the burn multiple, “puts the focus squarely on burn by evaluating it as a multiple of revenue growth. In other words, how much is the startup burning in order to generate each incremental dollar of ARR?” Their blog post has this great chart to show thumb rules on different burn rates:

The post deserves a read and will give you way more context on burn and how VCs use it. I think you’ll find burn calcs pretty useful for yourself too, once you set it up in your accounting system and put it on speed dial.

The post deserves a read and will give you way more context on burn and how VCs use it. I think you’ll find burn calcs pretty useful for yourself too, once you set it up in your accounting system and put it on speed dial.

It’s easy to “set it and forget it” and get tremendous insights into how efficiently you’re leading your growth.

- Churn

A VC recently counted 43 different ways to calculate churn. Don’t get caught up in that. We really want to know your (number of customers lost) / (total number of customers) in a given time period, such as a month. So do you! So this is one metric where founders and VCs both get trend as well as immediate operating benefit out of the number.

To be honest, as a founder, I knew I had other systems, like Callrail, that gave me more forward-leaning insights into churn before it happened. So like you, I had my focus on there, on preventing it. There may be a founder survival bias that makes looking at churn far harder than it should be. However, as a dry, bloodless number, it can help you make all kinds of cases for scaling, including:

- Where to invest your next dollars of revenue to maximize growth

- Features or products or customer segments to exit

- Where to make calls to key accounts in the weeks ahead to prevent similar churn when you see a trend

So I’ll say again, just do it. 🙂

By the way, churn is often segmented. If you are segmenting revenue, it’s useful to segment churn. If you have more than one type of customer, segment it. But generally speaking, churn erodes all your hard work so having it front and center for you and your team is key.

Startup metrics and seed rounds

I realize this can seem like a lot. But the value is clear for you–and it can put millions into your personal bank account If you get the metrics in place to forecast scaling properly in the next couple years, and those are clear to you and your partners in growth, you can share your insights with others in a common language that’s compelling.

Consider the founder that “wings it” until they have to have metrics. You can do it. But you’ll be competing with the founder(s) who had the discipline to put these metrics in place. It only takes a few days to set up, max, and a couple hours a month to manage. Those who invest 2-3 days getting their accounting systems lined up to deliver these metrics on forecasting scale were likely rewarded with a seven-figure seed round.

Those who get a significant seed round compete better, with:

- Better talent

- Cost advantages on pricing thanks to venture backing

- Recruiting top investor support for next rounds (that’s what a seed VC does)

So you can grow slow, until, of course, your customers are wooed away with better funded, faster competitors who are accessing top talent faster thanks to their bankroll, have more people hired in sales because they have more capital, and are able to enjoy price leverage in competitive bids.

Being a terrific operator with a visionary take on the market gets you far.

Being a metrics-driven operator takes you further. If you think you’re ready to talk to Valor about scaling success, please get in touch.